LIQUIDITY INSIGHTS: DEFINING CASH FOR AUSTRALIAN INVESTORS

Defining cash for Australian investors

Head of Asia Pacific Liquidity Fund Management

J.P. Morgan Asset Management

The definition of cash, while ostensibly straightforward – banknotes and coins – becomes increasingly challenging when the demands for higher returns counteracts the obligation to ensure adequate liquidity and the commitment to avoid losses.

As memories of the liquidity stress and market dislocation triggered by the global financial crisis faded, the range of financial instruments deemed acceptable in Australian cash products broadened dramatically. This was also a time when investors grappled with the challenges of outperforming attractive headline retail bank deposit rates.

Unfortunately, defining which instruments are truly cash equivalents is one of the most difficult tasks for modern corporate treasurers.

The Regulatory Dilemma

Globally, cash investors look to regulators and rating agencies to define and clarify suitable cash investment instruments and structures. This is especially true in the United States, European Union, and China, where the size and systemic importance of liquidity and money market funds (MMFs) made this a critical regulatory issue following the 2008 financial crisis.

These rules and regulations vary from prescriptive, listing specific approved and unapproved instruments, to abstract, outlining key sources of investment risk and limits to mitigate them. Regardless of the regulator’s philosophy, the ultimate goals remain the same – to ensure adequate liquidity and minimise the probability of losses. Over the past decade, global regulators have strengthened MMF guidelines. They now demand higher levels of liquidity, impose tighter investment limits and require increased diversification. For both retail and institutional investors, these new rules have raised the standard of MMF investing while significantly reduced the likelihood of funds suffering losses, albeit at the expense of lower potential returns.

In contrast to detailed global standards, Australian regulators have historically demurred the responsibility to define cash or the suitability of various instruments for cash investments. The Federal government’s unlimited bank guarantee during the Global Financial Crisis helped shelter the local financial industry while a long history of self-regulation encouraged investors to create their own definitions of cash and cash equivalents.

However, in 2018, a review of cash investment products by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) raised significant concerns about the level of volatility and risk in these products. Across the industry, the range of instruments and structures defined as cash varied enormously – as did returns. This created confusion for retail and institutional investors. In its subsequent report, APRA highlighted “examples in the industry where cash investment options appear to include exposure to underlying investments that would not generally be considered cash or cash-like in nature”1.

To encourage investment consistency and reduce the volatility of cash investment products, APRA concluded that “cash equivalents represent short-term, highly liquid investments that are readily convertible to known amounts of cash and which are subject to an insignificant risk of changes in value”1.

Cash means security, liquidity and return

The report signalled a tougher regulatory stance and additional focus on questionable cash investments styles. However, in the absence of detailed regulatory guidelines and exact definition of liquidity and risk, investor due diligence is still required to balance the need to preserving capital, while ensuring suitable levels of liquidity and maximising returns.

Three key steps in this process involve clarifying investment policies, creating well defined investment objectives and implementing cash segmentation.

Firstly, using an investment policy statement forms a solid foundation for cash investment decisions. A well written policy provides clarity, instils discipline and allows the organisation to successfully navigate shifting markets, changing regulations and evolving business needs.

Secondly, by defining short term investment objectives and the strategies for achieving them, an organisation can establish acceptable levels of risk, identify permissible investments and detail relevant constraints.

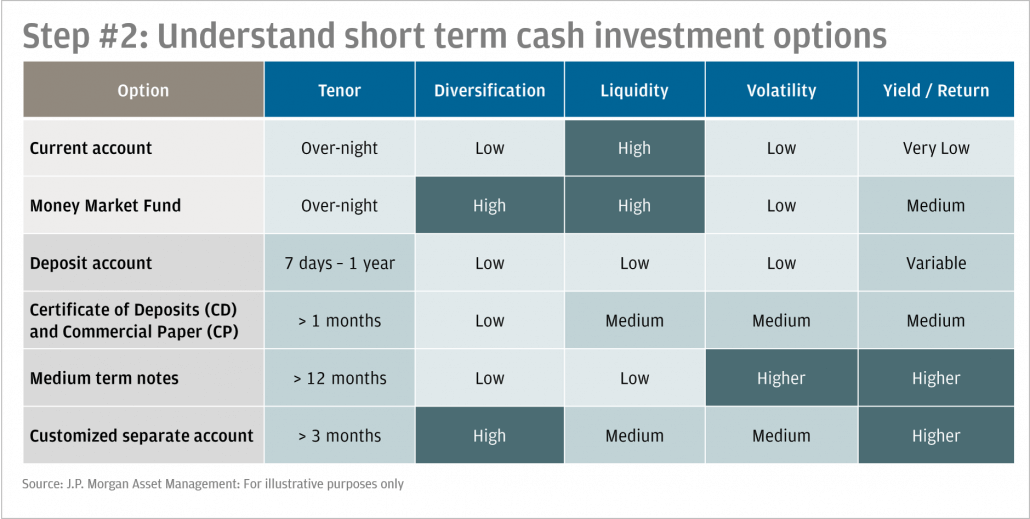

Finally, by putting cash into different segments, the organisation can optimise its investment choices – ensuring it has sufficient liquid cash to meet its daily needs while avoiding the opportunity costs associated with very high levels of liquidity and principal protection by diversifying across different types of cash investment depending on their level of liquidity, volatility, and diversification.

In Conclusion

The new APRA definition of cash has already prompted a significant reorganisation across the Australian cash management industry with several instrument structures being avoided and more conservative investment guidelines introduced. This, combined with more due diligence and understanding of the underlying risks by retail and institutional investors, should help the industry create a safer foundation for future growth.

To read more our liquidity insights, visit www.jpmgloballiquidity.com